I can’t open up Steam without getting assaulted by a screaming match between Cart Life and Cargo Commander. The two games live next door to each other in my library, and Braid, across the street, always keeps its window open to overhear. Later The Real Texas and A Valley Without Wind will come over for coffee and sotto voce gossip.

I can’t open up Steam without getting assaulted by a screaming match between Cart Life and Cargo Commander. The two games live next door to each other in my library, and Braid, across the street, always keeps its window open to overhear. Later The Real Texas and A Valley Without Wind will come over for coffee and sotto voce gossip.

Both games could be played by Patty Duke in different wigs and slightly altered speech patterns. One’s got pixel art; one’s cartoony! One’s black and white; one is colorful! One features interactions between characters; one leaves you isolated and alone! One’s got a chiptune soundtrack; one features a single country song on repeat! One gives you a choice of three characters; one has a single avatar! One takes place over a finite period of time; one stretches endlessly! Pitch it to USA, Characters Welcome: Cart Life and Cargo Commander are the original Odd Couple.

But at the end of the day, the two of them like having each other around. They may fight, and they may say ugly things, and they may hurt each other, but sooner or later, schmaltzy music is going to play and they’re going to express their appreciation for each other. They’re reaching towards the same goals: Both Cart Life and Cargo Commander take almost opposite tactics to come to the same conclusions the ways in which we can escape drudgery and transcend the loneliness of existence.

Cart Life’s designer Richard Hofmeier subtitles Cart Life, simply, “A Retail Simulation for Windows”. Much ink has been spilled on whether or not that descriptor is accurate. In fact, this was much of the focus of Nick Fortugno’s Well Played talk at IndieCade East this year. Fortugno stated that the “retail simulation” label was a “dodge”–perhaps suggesting that it was simply latching onto the genre’s popularity? It’s true that Cart Life doesn’t really fit the “retail simulation” genre–one which appears to contain games as disparate as Fortugno’s own Diner Dash and other, older games like Lemonade Stand and Dope Wars–but, in a way, that’s exactly the point.

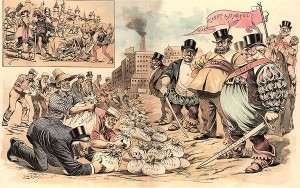

Line up every game that’s considered a “retail simulation”; five minutes with Cart Life will demonstrate that it’s the clear outlier. Its almost stubborn commitment to its own vision makes one almost wonder if the subtitle is less a sign that Cart Life wishes to fit into a certain genre and more a suggestion, by Hofmeier, that other games in the genre are shallow. Consider Diner Dash‘s story: Flo, a cute and perky businesswoman who decides to leave the rat race in order to fulfill her dream of owning a restaurant; it’s a lot of hard work, of course, but she’s not afraid to roll up her sleeves; she’s totally got this. Hell, Diner Dash is fun–it’s concerned with being a light casual puzzle game. Cart Life‘s minigames are optimized to be just uncomfortable enough that it’s never painful, but it’s very…tedious. At one point, Fortugno, smiling smugly, flashed a slide with the legend “Drudgery != fun”. The few people who have admitted to enjoying Cart Life‘s minigames themselves usually admit that they’re getting a perverse pleasure from it; I admit that my own love of Mass Effect 2‘s mining comes from a desire to be one of those weird people who likes Mass Effect 2‘s mining. Cart Life isn’t fun.

What Cart Life does is to take a look at Diner Dash and Lemonade Stand and find that genre is normally either so abstracted or rose-colored as to seem almost inhuman. Hofmeier creates a retail simulation which isn’t exactly pleasant to play; to that he has grafted an adventure game. And by giving the worker a distinct identity–family relationships, employment history, fears, etc.–the economics of the business intersect with the economics of life. One character smokes cigarettes in order to stave off hunger so he can concentrate enough to work a little bit longer in order to sell more newspapers so he doesn’t waste any money on unsold stock in order to increase his profits in order to afford cigarettes to calm his addiction for just a little while. The retail simulation, Hofmeier suggests, is incomplete: Your Lemonade Stander gets a hot meal from Mom in between turns; your Dope Warrior doesn’t have a dropping meter showing his intoxication level. Life in retail, when you get to it, is a nexus of needs and addictions and cost, and cart life leaves one fried and hollow.

And yet, the characters in Cart Life are able to attain a kind of dignity through their work. Success at the cart business represents something more for each character. For Melanie, it’s proof of independence and adulthood. For Andrus, it’s a new start in a new country. For Vinny, it’s a way to serve humanity in whatever way he can. Failure at their goals means failure at their dreams–at their lives. And yet there really isn’t a big deal made upon succeeding in any character’s scenario. Well, that’s Life. No one’s gonna throw you a party just because you remembered to pay the rent. Cart Life is less about achieving a “happy ending” for the characters than it is about getting these people into a sustainable lifestyle–one which may not be smooth sailing, but one where they can get the bills paid on time and maybe see a movie from time to time.

Less optimistic about the value of work is Cargo Commander, designed by Maarten Brouwer and Daniel Ernst. The premise is simple enough, and very different from Cart Life: You’re presented with a series of cargo containers, containing a selection of valuables and monsters, floating through space. The levels are procedurally-generated through whatever names you choose to give them, and the game tracks high scores for friendly competition. The goal of the game eventually becomes to scour sectors until you find one of every cargo type.

None of this is particularly innovative–Cargo Commander doesn’t really add any new elements to the table, although it balances its systems very well. There’s plenty to do, and enough secrets that it stays fresh, but while the game initially appears to have a steep learning curve, its structure becomes very quickly apparent and your morning routine develops. Wake up, grab a cup of coffee–feed that caffeine addiction!–check your upgrade bench, check your email, call the first wave of containers, explore and fight and collect, call another wave of containers, repeat until death or you get a pass to go to the next sector where you wake up, grab a cup of coffee–feed that caffeine addiction!–and so on.

This is Pac Man, this is Dig Dug, this is Asteroids. For a game to present itself as an unusual job–mining, or space defense, or whatever–is fairly standard, and so Cargo Commander‘s conceit–that you have a job in deep space doing salvage–isn’t unheard of. But like Cart Life, Cargo Commander is interested in the person you’re controlling. Cart Life takes a fully-realized character and drops him into a retail simulation; Cargo Commander takes a generic game character and wonders who he is.

Cart Life doesn’t need to go out of its way to justify why its characters are becoming cart jockeys–they’re all more or less at the end of their ropes financially, and carting appears, at least at first, to be the easiest way to stay afloat. It’s rough, and the deck may be stacked against you, but you can succeed at this job, and you can thrive. Cargo Commander makes no bones about the fact that cargo commanding is one of the worst jobs ever created. It’s lonely and isolated, it’s dangerous, you’re constantly fighting the mutated corpses of former cargo commanders, the pay isn’t great and the company doesn’t care if you live or die. One can’t really picture this existence being preferable to homelessness, and so the most logical solution is that he’s supporting a wife and a child back home.

And as the game progresses, you get emails from your wife talking about what life is like back home. And she warns you against playing online slots, which is quite strange considering that all the gambling activities in the game are completely free. You’re in deep space. And she talks about your promotion and hopes you’re not bored at the office–which is strange, because this is as far from an office job as you can get. And she jokingly–but not really jokingly, because she worries–hopes that you’re not flirting with your secretary–which is strange, because you’re all alone with only a single country song on endless repeat for company. And she mentions that she ran into someone who works at your company at the grocery store, and he wouldn’t look her in the eye–and you know, that makes perfect sense. Because the type of man who is willing to take a dangerous, horrible job to support his family isn’t going to be able to bear them worrying about him, and so he’s told them he’s a desk jockey working far away at Cargo Corp Headquarters, desperately hoping he doesn’t get killed and that, if he ever makes it back home, he’ll do his best to hide the trauma from them.

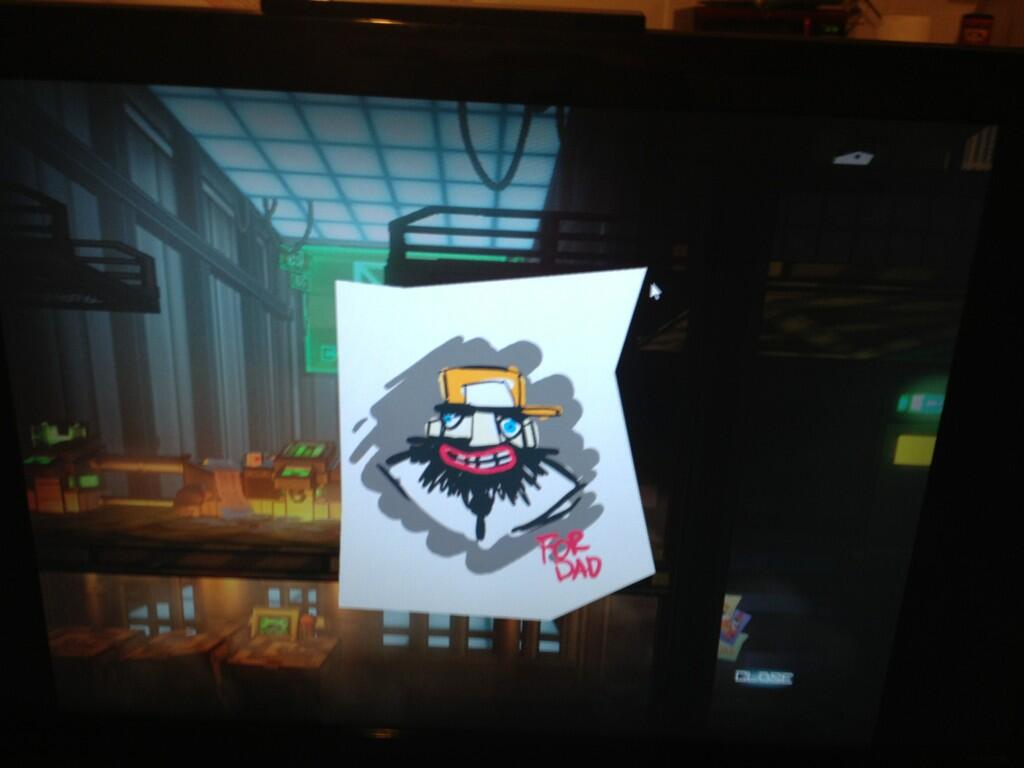

And then you get a notice that a package has been delivered to the headquarters–because that’s where you told your family you were working at, right?–and they’re happy to forward it on to you for a small fee, and so you sell some of your hard-found cargo in order to pay the fee, because what could it possibly be?, and it finally gets there after a couple of days, and inside is a crayon drawing, of you, from your son, with the note “FOR DAD” scrawled on it. And as the game goes on, you get more notices, and the fee gets greater and greater each time, and you know what, it doesn’t really matter, and you stick them up on the wall of your ship.

And then you notice that the drawings are tied into the achievement system–that when you earn certain ones, the drawing your son gives you is related somehow to it, although since he’s been told you’re an office guy you’re in a shirt and tie and surrounded by coworkers–and you begin to earn achievements just to get these little scraps from home. And then you notice that other achievements remind you about times with your wife, and then you notice that the descriptions of some of the cargo items give you other memories–you find a “serial killer sweater” which is not unlike the awful one you wore on your first date with the woman you eventually married, a pair of sexy heels that remind you of your honeymoon–and it becomes clear that this character views everything in terms of the wife he misses, the son he cannot watch grow up, the home he cannot live in, the family he cannot enjoy, and then suddenly Cargo Commander becomes a document of the extreme sacrifice that this guy is making. In a way, the man’s wife and child are held hostage by the company: Work harder, hard worker, or you’ll never see your family again.

Both Hofmeier and Ernst have real-life inspirations for their work. Hofmeier’s random curiosity about street vendors led to research and respect–in many ways, Cart Life is a Studs Terkel-esque work of creative journalism. The park has a statue of Ruby the Knish Man–it sounds like a lost Malamud or Singer story. He was a real New York City knish vendor. The whole game is, in a way, Hofmeier’s attempt to build a statue for an oft-ignored group of people whose stories he felt moved to share. Ernst based his game partially on memories of his father, who worked in a dangerous factory he was never allowed to see as a child, the deep space setting an exaggerated version of that life. In many ways, Cargo Commander represents an opportunity for Ernst to thank his father for the sacrifices he’s made for his family–but in translating the setting and not even naming the cargo commander, Ernst universalizes it. It has been the traditional role of men to place themselves in dangerous, life threatening situations so that women may enjoy the privilege of not having to. And we’ve all met at least one person who’s living in the US in order to earn money to send back home. Critiques of patriarchy from the point of view of the housewife–that her options are extremely limited–are all valid, and all necessary. And yet Cargo Commander shows us the flip side–both men and women are victims of a system which exploits its workers without caring about them. At one point, the computer sending you emails each time you go up a level breaks down; the traditional “Hello INSERT EMPLOYEE NAME HERE, your INSERT ACCOMPLISHMENT HERE has been recognized” joke is made, and it’s particularly cruel because you don’t even have the dignity of being able to pretend that a piece of boilerplate form text is an actual person.

And yet, much as people see Cart Life as a depression simulator, as dark and as cynical as Cargo Commander can be, in each is the hope of human connection. A job running a food cart is unsteady, unstable work which hurts the spine and fatigues the brain–and yet, a chat with a regular customer, a random good tip, someone finding something you made delicious–that makes it all worthwhile. And the Cargo Commander may be sacrificing everything for his family–but it wouldn’t be a sacrifice if it wasn’t awful, and you know what? He loves them enough that he doesn’t even really think about it. Both games take place inside inherently corrupt systems which give no safety net to its lowest members, and either game can make one receptive to arguments against capitalism. And yet, until change occurs, we’re living in a world of Work, and of Work which may not necessarily be fulfilling, or even necessary–I can think of no possible future that would employ someone to find ugly sweaters and bent forks. Human connection is what makes life in a world of drudgery bearable. And so, one leaves Cargo Commander and Cart Life, neighbors, enemies–and friends–with a strong impression of empathy, and of love.

Work Harder, Hard Worker

Work Harder, Hard Worker Review: Corn Zone

Review: Corn Zone Flying Man

Flying Man For The Cost of Bioshock Infinite, You Could Buy 60 Copies of Miner Dig Deep (More If You Count Tax)

For The Cost of Bioshock Infinite, You Could Buy 60 Copies of Miner Dig Deep (More If You Count Tax)